Honoring Those Who Came Before Us, Isaac and Ann Grey Holleman

by Susan White, Holleman Genealogists and Historian

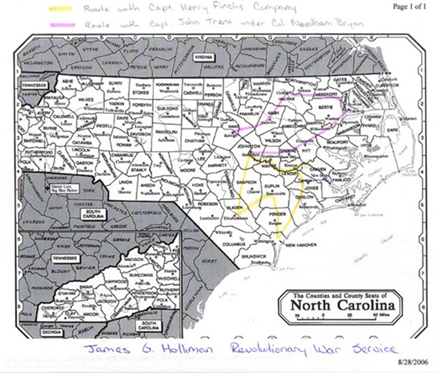

Editor's note, this is the climax of the Isaac and Ann Grey Holleman story which first surfaced in this blog when your editor shared lunch with Sandi Royal in 2013. Descendants of Josiah Holleman of Isle of Wight County, Virgina, both African-American and European American, have been jointly researching this American story for over a decade. On Saturday, March 1, 2025, Isaac Holleman descendants visited the site of Isaac's farm, one mile south of

the town of Windsor, Virginia, off Route 608. Susan White explains how the story unfolded. - Glenn N. Holliman

Family

Our white Holleman ancestors in Isle of Wight, Virginia,

enslaved people. We don’t know if that

practice started with Christopher Holleman (Holliman, Hollyman), our first immigrant, but it could

have. Christopher grew tobacco, a labor-

intensive crop, and must have needed helpers for his harvest. My fifth great grandfather, Josiah Holleman,

(1771-1848) enslaved at least eleven Black men, women, and children during his

lifetime, including Isaac Holleman (1818-abt 1898), the main subject of my family

genealogical research for years. He

fathered Isaac, and at least one other Black man, James (1825-unk) with an

enslaved Black woman. Isaac’s story was shared in public at a presentation sponsored by the Isle of Wight Historical Society on June 22, 2024 at the Georgie Tyler Middle School, Windsor, Virginia.

Isaac’s descendants, have been enlarging this story that

continues to broaden. Glenn Holliman

first mentioned Isaac in his 27 June 2013 blog post where he spoke of Sandi

Royal’s research and retelling of family lore, that Isaac “ran off with Ann

Gray, a white woman,” whose family was against the relationship. Sandi spoke of a picture of a “white woman”

that hung in her family’s house for years.

I learned of this story in 2016, from Glenn, at a Smithfield, Virginia

Holleman family reunion.

Glenn N. Holliman and Susan White at a 2016 Isle of Wight conference.

At that time, I had just begun to research my own connection

with Josiah Holleman, who was my fifth great grandfather. One of his sons, William Henry Holleman

(1795-1834), was my own Holleman ancestor, and he was an enslaver, as

well. Identifying the relationships

between my Holleman enslavers and enslaved people around Isle of Wight county

in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries has been and continues to be

difficult. We discovered some of the truth of Ann Gray, however, and where she

came from, most likely Nansemond County, VA.

Sandi Royal, my daughter Lea Marshall, my brother, Eddie Gallier and I have used the tools of DNA,

paper records, National Archives aerial photography, and sometimes pure dumb

luck to dig into this story.

Isaac fathered

children first with Malinda Pretlow, a free Black woman, and then with his

wife, Ann Gray. Descendants from both

unions have connected over the past few years to learn more about their roots.

Sandra Royal

Nonnie L. Holliman

Kenya Allmond

The Family Farm in Windsor

After their escape from enslavement during the Civil War, Isaac and Ann Holleman bought a 50 acre farm in 1871, about

a mile south of the town of Windsor, Virginia.

This was no small feat. They owned

their farm, did not sharecrop, and

the farm stayed in the family until 1963, when James Trueheart Holliman, a grandson of Isaac,

sold the farm to W. T. Joyner. It was

sold one more time before the Norfolk and Western Railroad bought it in the

early 1990’s.

The 1880 agricultural schedule reveals his livestock and

crops and the effort Isaac was expending to provide for his family:

1 horse, 1 mule, 1 working ox,

1milch cow and calf, 9 swine and 13 poultry

100 bushels of corn, 20 bushels

of sweet potatoes, 50 bushels of apples, 50 bushels of peaches.

He cut 60 cords of wood the year

previous.

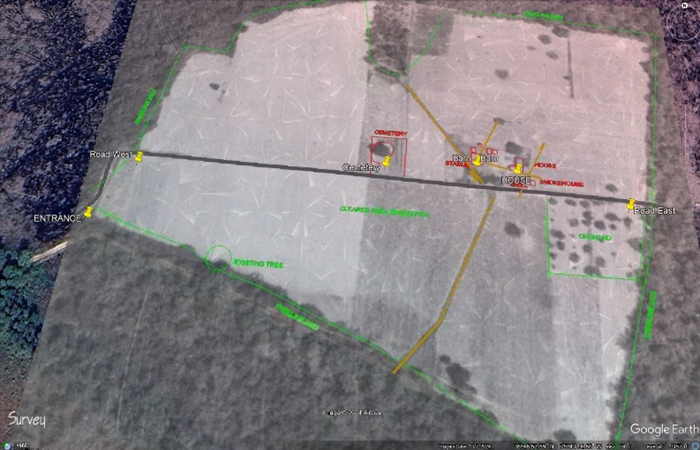

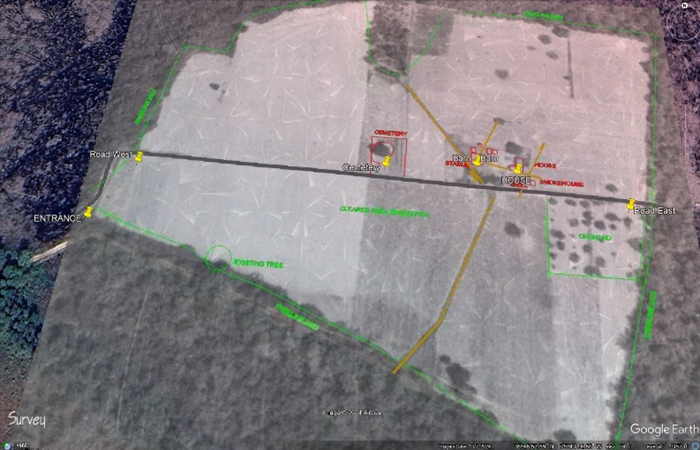

About 2023, in one of those lovely serendipities of

genealogical research, Jim Henderson of the Isle of Wight County Historical

Society discovered an old file on his computer that another Society member must

have shared with him at some point along the way. The file was a part of an

environmental impact study undertaken by William and Mary Archaeological

Department for the Norfolk and Western railroad (now Norfolk Southern Railway)

as it was buying the farm from the Joyner family. Another stroke of good fortune was that the archaeologists

met Reverend Arthur Holleman, a great-grandson of Isaac, who knew the farm when

it was in the family, and enlisted his help to identify what they were finding

in their labors.

To read the report is

to marvel at what Isaac Holleman accomplished.

Unfortunately, as time passed, the farm became lost to the descendants

who lived in the area. No one living

knew exactly where it was. On two different occasions, a group of Hollemans attempted to find it using the maps

in the Norfolk and Western study, but we were not very good at reading the

many-times-copied maps. The third try

was successful, and luck was with us again.

In November, 2023, as the county farmers were harvesting

their cotton crops, we discovered the dirt road off of Route 608 in Isle of

Wight, and the chain across it was down.

We were able to drive down the rutted road and found the farm. About 8 bales of cotton were stored at the

edge of the field, waiting to be taken to the cotton gin. Jim and I got out of the car and began to

walk the field of cotton stubble. It was

a beautiful day and we were very excited.

Jim wondered who farmed the field?

Maybe we could find out?

It was

late in the day, but Jim thought we should drive over to the cotton gin

facility, to see what we could find out.

Luck prevailed again. The owner

of the gin gave us a name of possible farmer, and I called him. He was not the one in this case, but he gave

us the name of who he thought might be our man, and Success! Mike Griffin was the farmer who still leases

this land from Norfolk Southern Railway.

He has been farming the field since about 1995.

Susan White and Lea Marshall

In January, 2024, my daughter Lea and her husband, Will Kerner, visited the farm, this time hoping to obtain more

pictures. Will has a drone camera, and

he was able that day to take aerial pictures.

It was a cold, dreary day, and this time the chain at the entrance to

the dirt road was in place and locked.

We had to walk the long, muddy road to come to the field, rather than

driving.

Courtesy of William Kerner, this photograph shows a dirt road separating the field of standing water (left) from the green field in the upper center of the photograph. Windsor is the white border upper right. Jim Henderson has encouraged us consistently for several years in uncovering

Isaac Holleman’s story. In 2024, he invited us to present what we

were learning to the Isle of Wight Historical Society. Our group, in particular, Sandi Royal and Nonnie

Holliman, who are both Isaac descendants, agreed. My daughter, Lea, my brother, Eddie Gallier, and

Glenn Holliman were also eager to share the story.

Eddie Gallier (pictured) is an avid modeler, particularly in constructing model

train layouts. The man has skills. I asked if he would help us to create a model

of Isaac’s farm. He agreed, and in 2023,

in order to learn more about the farm, he contacted the U. S. National Archives to inquire about U. S. Department

of Agriculture aerial mapping. Thanks to

the generosity of several family members, Eddie obtained the 1930’s-1950’s

aerial photos of the Holleman farm from the Archives.

1938 aerial view of

farm with structures in the middle of the picture.

He also had the N and W study in which to refer. Eddie then created the farm layout in a HO model railroad gauge showing the house, barn, outbuildings, well,

smokehouse, the family graveyard and the orchard. He photographed them all, so they could be

included in our presentation.

Model of farm by Eddie

Gallier

On June 22, 2024, as part of Isle of Wight Historical

Society’s Juneteenth observation, we told “The Extraordinary Life of Isaac H.

Holleman” at Georgie Tyler Middle School.

About eighty people attended, many of them descendants of Isaac,

Malinda, and Ann.

Season and Weather

Our research group has visited various Holleman related

sites in Isle of Wight over the past 3 to 4 years.

One day was in March, bitter cold and snowy. Then a couple of summer days where I got chigger bites in the Tyler Cemetery. Then another beautiful late fall

day, and a dreary, depressing January day.

Doing so, however, revealed another layer in Isaac’s life. He had encountered all kinds of these days during

his life in Isle of Wight. We were

fortunate to encounter them, also.

Now we know where the farm is and can visit, but because the

Holleman farm is an actively cultivated field, we visit with full knowledge of

season and weather and respect the farmer's work. We can visit from

early December until mid-March. We have trudged through mud and crop stubble, as Isaac and his family did. This spring we rescheduled twice a trip due

to snow.

This past March we finally made it on a warm, early spring day,

occasionally windy, but not uncomfortable.

As we crossed the swampy area at the entrance of the field, we heard frogs. We heard the headwaters of Ely Swamp

gurgle. You could hear the wind. Below muddy fields and swampy bogs.

Prior to

our trip, my brother had helped me load coordinates into my phone Google map,

of the family graveyard, the house, barn, and the orchard.

We made our way across the field, hammered stakes into those

sites. We stopped at the graveyard site and prayed a prayer that Nonnie

Holliman had written for us.

Right to left:

Nashawn Holliman, Alexander Holliman, Kenya Allmond, friend of Kenya, Sandi

Royal

A Prayer of Remembrance for

Ancestors at the Holliman Farm, March 2025

Dear God and Ancestors,

We gather in reverence and gratitude, remembering your

spirit, your wisdom, and your strength. Your journey through life laid the

foundation upon which we stand, and your legacy continues to guide us with

every step we take. We honor your sacrifices, the dreams you nurtured, and the

love you bestowed upon our lineage. Your stories, though sometimes untold, are

woven into the fabric of our existence, and we cherish the lessons they impart.

May we always strive to live in a way that makes you proud, carrying forward

your virtues and values. As we reflect on your lives, we seek your guidance and

protection. Help us to face our challenges with the same courage you displayed,

and to celebrate our triumphs with the same joy you felt. May we be ever

mindful of the paths you forged, and may our actions today honor your memory. In

moments of doubt, may we feel your presence, and in times of celebration, may

we sense your joy. Your spirits dwell within us, a constant reminder of the

enduring bond we share. We are eternally grateful for the roots you have

planted and the legacy you have left behind.

With deep respect and love, we remember you. Amen.

By

Reverend/Superintendent Nonnie L. Holliman, Great Grandson of Isaac and Ann

That day we could be

where Isaac and his family lived and died.

It was a very good day.

.jpg)